In search of architecture that belongs

Dualchas Architects and Heb Homes have very kindly been supporting the work of Tobar an Dualchais over the past two years. In this piece the architecture firm’s co-founder NEIL STEPHEN discusses the misconceptions around authentic Highland architecture, drawing on the personal experience of Duncan ‘Stalker’ Matheson of Kintail, a key contributor on the Tobar an Dualchais website.

What makes architecture authentic and belong to a place?

This question reminds me of when my brother and I were discussing the characteristics of the blackhouse with master thatcher and stonemason Duncan “Stalker” Matheson from Camusluinie in Kintail.

He told the story of how a man interrupted him while thatching to tell him how disappointed he was to see him using metal nails as they were “not traditional”.

Duncan’s reply was to admit that he was not the most attentive student at bible studies, but “was Jesus Christ himself not nailed to the cross?”

What is seen as traditional and “authentic” can be about perception, or sometimes ignorance.

Duncan would make the point that vernacular architecture was not primarily about style or materials but practicality.

Thatch was used in the Hebrides because it was, literally, the material to hand. It was laborious work and required vigilant maintenance.

But when people could afford metal sheeting they used this instead as money bought you precious time to spend on something else.

The practical nature of construction was something Duncan was aware of because he not only built using traditional techniques but lived in a blackhouse.

He dismissed the academic theory that the walls of blackhouses were rounded to deflect the wind and were developed from the rounded beehive hut form.

He said: “Have you ever tried building a thatch on a corner?”

He also explained that the reason the walls of the Hebridean blackhouses of the Western Isles were so much thicker than the ones on Skye was not because of a stylistic divergence.

It was because Skye had more trees.

The cruck frame of the Skye house connected to a vertical timber post that sat in a holster in the stone wall, taking the load downwards.

The Western Isles is almost treeless, so there was a need to reduce the use of timber – but there is plenty stone.

So the cruck frame had no connecting vertical post and instead sat on top of the inside of a huge wall head. The thicker wall then acted as a buttress to the horizontal forces of the roof.

But the buildings did share fundamental characteristics.

They sat low against the storms with the openings to the east, facing the morning sun with the back to the prevailing wind.

The plan was one room deep, making the roof easy to span so large timbers were not required.

And because they were built from the materials of the landscape; the stone, the timber, the reeds, all of them blended in seamlessly.

If the blackhouse is a response to the economic, topographical and climatic realities of a place, what then is a kithouse?

Imported timber frame replaced stone as it was simpler and cheaper to build.

Slate or metal roofs replaced thatch because they are longer lasting and less labour intensive.

So is it authentic, vernacular architecture?

Well it depends.

A vernacular building responds to context, whatever it is built from. A brochure design that is at home in the suburbs of an American city will seem out of kilter on a Hebridean island.

Is it a practical response to economics? Perhaps. But does it respond to context? To the weather, the landscape and story of a place?

When the hurricane force winds of the great storm of January 5th 2005 hit the west coast of Scotland, most houses suffered damage.

But not the remaining thatched blackhouses. As slates were ripped off houses and scattered to the four winds, the thatch of the blackhouse was left unruffled, complacently intact.

The lesson was that our predecessors understood where they were building.

Roofs sat low, there were no projections to catch the wind.

A steep pitch and projected eaves is great for casting off snow, but not something that is required in the temperate but fierce climate of the Hebrides.

Architecture critic Jonathan Meades ignored the blackhouse when he visited the Western Isles to make his programme the Island of Rust.

The islands’ modern houses he described as “anti-architecture”, as if they were deliberately trying to affront the beauty of the landscape.

But he didn’t dwell on this. Instead he found beauty in the ingenious self-designed and built sheds and sheilings of the crofts, the rusting metal and weathered paint giving them a beauty and authenticity.

Each one had a story, a connection; each one was cherished by a family or community.

And as he pointed out, none would make it into a hardback publication about architecture, none would seem worthy of record by Historic Scotland.

The architecture that Duncan Stalker built did get into some books but is often viewed as a cultural curiosity of a bygone era.

He died in 2010 and if you look him up online you will see that he is remembered as a Highland gentleman who respected and protected Gaelic tradition, was a master of trades and a great “seanachaidh”, or storyteller.

You can hear him tell his stories in his beautiful Gaelic on the Tobair an Dualchais digital resource.

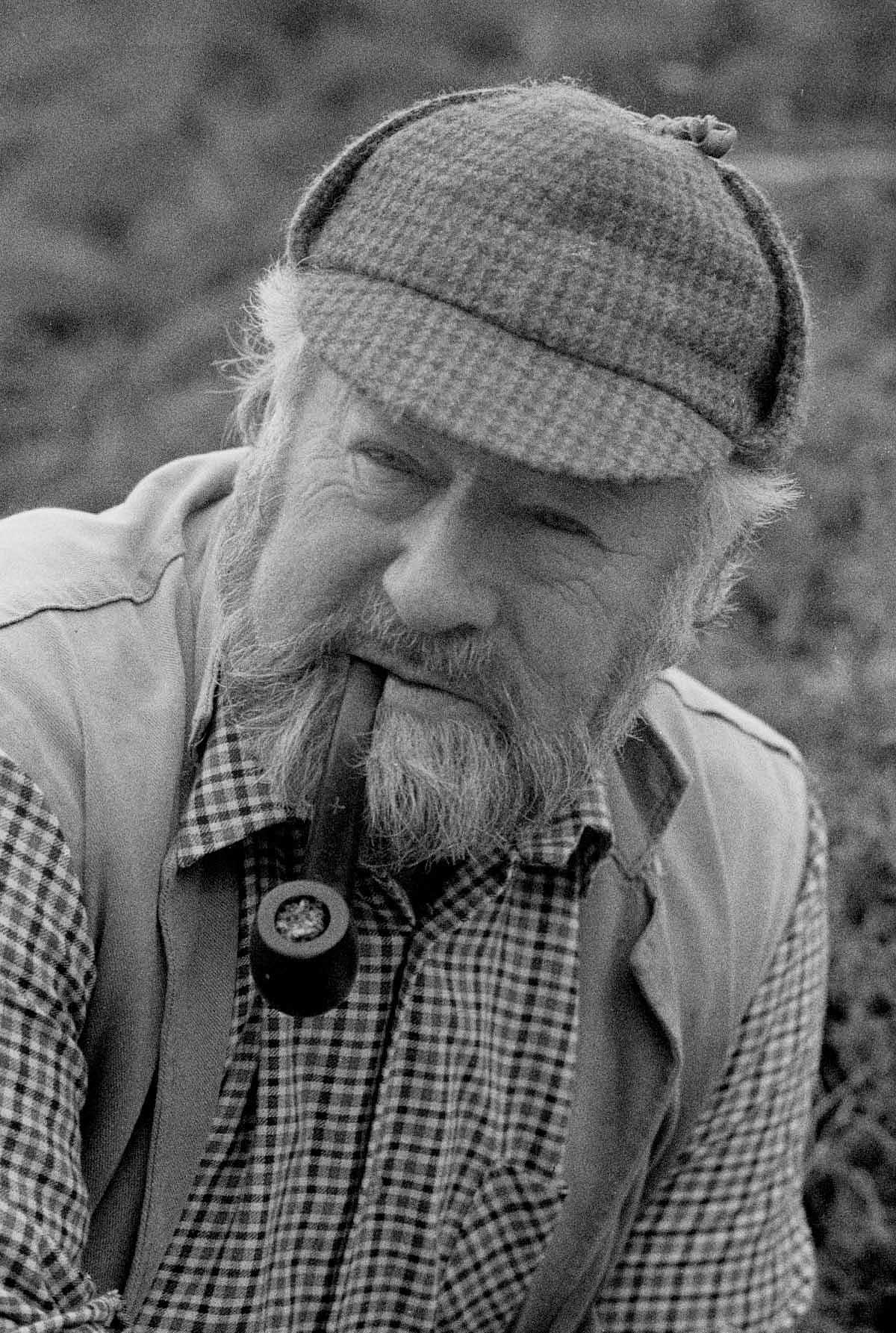

When myself and my brother met Duncan around 30 years ago he was still a working man, although nearing retirement, and was thatching a cottage near Dornie.

He had prodigious facial hair and huge hands with thumbs as meaty as ham houghs.

While speaking he sat on a stool and used a pen knife to scrape skelfs from a rope of tobacco into his pouch.

When we described him to our grandmother she became emotional as she remembered her father, who back in the early 20th century on Skye would sit and do the same thing.

It is these associations that can give continuity to a culture.

Whether it is the telling of a story, the singing of a song or the speaking of a language, there is a thread that takes us to a time past.

And so it is with architecture. A design can respond to climate and location, but it can also make a connection to a person, a family and a community.

It is our job as architects to continue telling this story, to update it for modern times.

Yes we have to face the climate emergency and embrace new technology.

But first we must look around us, understand the context, and learn from what has gone before.

Perhaps that’s what makes architecture authentic and belong to a place – whatever the materials we use.

Notable recordings of Duncan ‘Stalker’ Matheson on TAD:

In TAD ID 105499 Duncan sings ‘Cha b’ e Dìreadh na Bruthaich’ which tells the story of Fearchar mac Iain Òig (Young Fergus son of Iain) of Kintail who became a fugitive for seven years after he murdered the factor who had taken his cow and copper kettle to settle a debt.

In TAD ID 85731 Duncan is recorded at the site of a lifting stone near Camus Luinge where he tells an anecdote about local strongman Duncan MacRae who was killed at the battle of Sheriffmuir.

In TAD ID 65552 Duncan tells the story of two men, Donald and Angus, from Sleat who go to the Black Isle to buy whisky.

On travelling home through Glensheil they hear music coming from the ground and discover fairies. Angus joins the fairies whist Donald goes back to Sleat. A year later Donald goes back to find Angus in Glenshiel still dancing having only felt the passage of a day!