Remembering Iain Fhionnlaigh – the Berneray fieldworker

Sabhal Mòr Ostaig and Tobar an Dualchais PhD student, Liam Alastair Crouse, examines the life and work of Ian Paterson who was key in helping to collect and document the folklore of the island of Berneray.

“Cha do chuir thu siud air, Iain?!” Catrìona bawled to her brother, incredulous that his tape-recorder had been quietly logging her stilted retelling of one of their father’s favourite jokes (Track 42144).

Of course he had: Ian Paterson had a habit for taking advantage of family cèilidhs and community gatherings as recording studios.

Just like the time when his older sister, Bessie ‘Beasag’ Paterson, had a party thrown in her honour at the Newton House Hotel when she received a British Empire Medal for her many years of work as switchboard operator in the Isle of Berneray, their home.

It is not hard to imagine him prowling the event, recorder in hand, searching for a song or a good joke.

He caught George MacDonald just as he started on a joke about a minister, the audio growing louder and clearer as the device is pushed to his mouth (Track 65293).

Sometimes his ‘informants’ – mostly friends and family – fought back. “Agus càit’ a-nise an do rugadh t’ athair a Mhòrag?” (“Where was your father born, Morag?”) he once asked his aunt Mòrag Aonghais Iain, trying to maintain some form of formality for the recording’s sake (Track 73477).

“Rugadh anns an leabaidh e, tha mi a’ smaointinn…” (“He was born in bed, I think…”) came her riposte. After all, hadn’t she recorded all this family history for him three years previously (Track 49911).

Others went to greater lengths. Ceit Dix, the august storyteller and poet in the island, would tease him in verse (Track 50579):

Thog e am bogsa air mo bheulaibh

Feuchainn an lìonainn e le breugan

Cha robh sin cho doirbh a dhèanamh

Bha Catrìona dlùth orm.

He put the box in front of me

To have me fill it with lies

That wasn’t too hard to do

As Catrìona was near me.

He undoubtedly understood the poem in the way it was meant – as a compliment. He understood much about the Gaelic culture of Berneray, his own cultural inheritance, his dùthchas. But he may have encouraged her to change the lines; the version he eventually submitted to Tocher, the magazine of the School of Scottish Studies, notably excludes the verse:

Ach ma chluinneas iad ’n Dùn Èideann

Mar a bhios Wally falbh air chèilidh

’G òl an fhìon air a co-chreutair

Bidh iad fhèin a’ diùmbadh rium.

But if they hear in Edinburgh

How Wally [Ceit’s nickname] goes visiting

Drinking other’s wine

They sure will be unhappy.

She made other derisive poems too, including Do dh’Iain Chan Eil Diù Agam (‘For Ian I Care Not’) which remarks on how he would continually pester her – 26 years his elder – to sing her impromptu compositions:

Thug e orm bhith seinn nan òran

Is an guth agam mar ròcais

Nuair a bhiodh iad cruinne còmhla

’G ithe ròn aig Sùlaisgeir.

Do dh’Iain chan eil diù agam

On rinn e fhèin cùis-bhùirte dhìom

Do dh’Iain chan eil diù agam.

He made me sing the songs

Even though my voice is like a crow’s

When they would be together

Eating seals at Sùlaisgeir.

For Iain I care not

Since he made me a laughing stock

For Iain I care not.

Tellingly, by the final recording of that song in 1974, she did sing it for him (Track 58921).

He had that effect on people, a knack for making them feel at ease. They would have been too polite to reveal their mischievous side to a stranger.

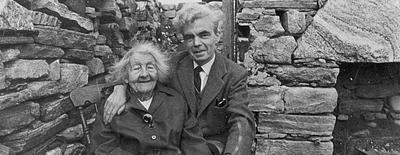

But he was only Ian, that shy boy they had known in his youth. It did not matter so much that he had gone to the mainland, first to Fife as a teacher and headmaster, and then onto the School of Scottish Studies as a transcriber in 1965.

To them, he was Iain Fhionnlaigh Aonghais ’ic Iain Shomhairle Thormoid, son of Fionnlagh Paterson of Geodha Dubh and Catrìona MacCuish of Cùl na Beinne, who had a shop and ran the ferry.

There were six children in the family, all of whom left their own mark on their community.

There was Christina who took over her father’s position as registrar, and Seonaidh Angus became ferryman. Beasag was the switchboard operator.

When Ian would return home on his holidays to undertake fieldwork for the School of Scottish Studies in his own time, he would put to good use his family connections.

Much of his immense collection of folklore and oral history derived from his family and neighbours.

Learning was in the family’s blood. The progenitor of the Paterson family, known as Clann Shomhairle, is believed to have come from the Black Isle in the late seventeenth century as tutor to the children of Sir Norman Macleod of Berneray.

It is little wonder, perhaps, that Ian became headmaster. Or that he had such a grasp on Gaelic language and literature.

He was a bard, writing down his own poetical musings in a little notebook, Leabhar nam Prannag, or putting them on tape, more for himself than anyone else (Track 103927).

His works grant a clear insight into his thoughts and reflections.

From the description of a childhood hunting expedition, where he praises in traditional panegyric his younger brother Ruairidh for ably sourcing food for the table, to a short, jocular rhyme ribbing one of his informants, Niall Chaluim Fhionnlaigh, who succumbed to a fit of coughing during a recording session:

Niall Chaluim gun anail

Le casad na amhaich

Is feumaidh e salann

Mus gabh e dhuinn rann.

Tha ’anail air a tachdadh

Le casad ga bacadh

Is chan eil cungaidh no acainn

A bheir faochadh cho math dha

Ri salann san àm.

Niall Chaluim is gasping

A cough in his throat

In need of salt

Before he gives us a verse.

His breath is choked

With cough obstructing

And there is no cure or remedy

Which will give him relief

Than salt just now.

Such off-the-cuff sarcastic lampoons provide an exceptionally unique window into the inner workings and relationships composing a close-knit community, buttressed with humour and camaraderie.

In total, Ian produced some 3,200 recordings, now available on Tobar an Dualchais, marking him out as one of the major fieldworkers within the School of Scottish Studies Archives. Nearly half were made in the island of his birth.

Due to his skill, community connections, kindness, and enduring passion for the Gaelic oral tradition, the Isle of Berneray boasts one of the most complete folklore collections from the islands during this period, between 1960 and 1980.

It is an important legacy, and one which will only grow with time.