The journey of the swelling hag

Liam Alastair Crouse is a first-year PhD student at Sabhal Mòr Ostaig UHI studying the folklore of Uist, in the Outer Hebrides, in partnership with the Tobar an Dualchais/Kist o Riches digital archive. This article, which was prepared with the help of Prof Domhnall Uilleam Stiùbhart, is the first of future pieces detailing aspects of the PhD research.

Traditional tales and legends form a rich line of inquiry in folklore. In the Highlands and Islands, the rich collections of oral lore made from the 1850s to the present day present a valuable opportunity to consider how and why Gaelic folklore is passed down and adapted through time.

Sometimes we can follow the journey of a specific story by comparing earlier texts from the great collections of the 19th century with later recordings, especially those in the School of Scottish Studies archives available online at the digital archive Tobar an Dualchais. We catch characters, plots and individual episodes changing to reflect new environments, audiences and times as each version is transported by the carrying stream.

How a story changes informs us about the people who tell them – their culture, beliefs, and worldview. A setting may be changed to make a story more appealing to a local audience. An episode may be omitted because it isn’t seen to be relevant – or because it is too sensitive. The same story may be repeated because it is an effective warning: be wary of the wilderness lying beyond our township’s boundary.

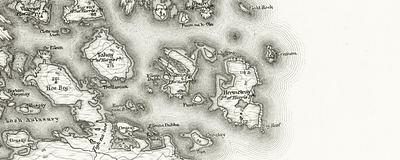

With the help of Tobar an Dualchais, we can follow one story’s journey from Highland moor to the island of Hearmatraigh, near North Uist, in real-time. Folklorists call this kind of story a migratory legend: where the same type of story is told in different areas, but with different settings and characters, localised where it is told.

Catherine Dix, or Ceit an Tàilleir, was a remarkable storyteller who contributed hundreds of items to the School of Scottish Studies Archives. Born in 1890, Ceit spent her early life in Beàrnaraigh, before moving away for work on the mainland at the age of 14. After a prolonged time away, she returned with her family to the island at the start of World War Two. She was recorded extensively during the 1960s and 1970s.

_-_via_EM.jpg)

One traditional story features a shepherd and his dog who stay in a shieling overnight. A hag arrives to warm herself by the fire. She swells to the size of peat-stack, remarking that it’s only her ‘plumage’ rising with the heat. The hag attacks the shepherd but is driven away by the dog. The story is often called ‘m’ iteagan is m’ oiteagan’ (roughly translated as ‘my feathers and plumage’): the phrase appears in most variants of this tale.

Ceit recorded the story on at least three occasions in 1968 (44765), 1976 (63176) and 1978 (71670) by Iain Paterson (Iain Fhionnlaigh), himself a native of Beàrnaraigh employed as a collector for the School of Scottish Studies. The 1968 recording is transcribed in the excellent 2019 publication by Ceit’s granddaughter, Alison, Ceit an Tàilleir.

Ceit clearly enjoyed telling the story, but during a decade of performances it changed its setting: from a nondescript Highland moor in 1968, to an unnamed island in 1976, and finally to Hearmatraigh in 1978. A story, originally set on the mainland, is gradually reworked by the storyteller, perhaps to make it more appealing to an island audience.

It’s in the nature of migratory legends to change – it’s what makes it easier for them to migrate in the first place. But can we also trace where the story came from? Where did Ceit first hear her story: in Beàrnaraigh, or elsewhere?

Folklore recorders are trained to ask about where tradition comes from. At the end of every story, Iain Paterson would ask Ceit where she heard the story. In 1968, she mentioned her father, Archibald Macleod (Gilleasbuig Tàillear mac Iain Dhòmhnaill) from Baile Mhàrtainn in North Uist. but in the 1978 recording she offered an extra explanation: the story in fact came from Archie MacColl of Ardtur in Appin, where she worked on a farm between the ages of 14 and 18 years. Paterson, clearly intrigued, asks how the story came to be set in Hearmatraigh. Ceit replied that Archie MacColl had heard the story from a boy from the Outer Hebrides who was working for him.

It’s interesting that Ceit maintained here that the story was set in Hearmatraigh in both versions she heard – the one from her father and the one she heard as a teenager working in Appin. In her first recording she had set in the Highlands.

By comparing this story and its episodes to similar ‘migratory legends’, we can try to trace how it might have spread. The villain of Ceit’s story is the ‘Swelling Hag’. This redoubtable character is met with in a type of traditional story that once was told across Eurasia. It is known by folklorists as ‘The Two Brothers’.

In the Scottish Gàidhealtachd, we have a version of ‘The Two Brothers’ recorded in Beàrnaraigh. It is called ‘Cailleach na Riobaig’ (‘the hag of the strand of hair’) and was collected in 1859 for John Francis Campbell’s ‘Popular Tales of the West Highlands’ project. Despite similar wording between the two tales, Ceit’s story contains episodes not present in the 1859 tale, episodes resembling other versions of the story collected on the mainland, east of Appin.

On the whole, Ceit’s story is more similar to these mainland versions than anything recorded in the Outer Hebrides. Although she told Iain Paterson in 1978 that both versions of the story she had heard were set in Hearmatraigh, it may be that, to make the story more attractive to an island audience, Ceit deliberately relocated an originally mainland story to the Sound of Harris. This comes through in the changing setting of her three versions of the story.

But why Hearmatraigh? In relocating her story, Ceit chose a location which preserved the kind of setting in the original mainland story. She keeps the shieling, an outpost of civilisation in the wilderness where many stories tell of conflicts between human society and the supernatural.

Hearmatraigh might have been chosen as it was one of the principal islands where Beàrnaraigh folk would stay in shielings for short periods to hunt, fish, and harvest peat. One recording on Tobar an Dualchais (Track ID: 14195) notes that the bothy on Hearmatraigh was built using lime-mortar: this construction technique would have made it stand out among other island shielings built of stone and turf.

The Hearmatraigh settlement was centred around the natural harbour known as An Acairseid Mhòr. It is very likely that the fishing station from the time of Charles I mentioned by the Hebridean author Martin Martin (1703) was located here. Could the fishing station’s ruin have been later repurposed as a shieling? This may explain the use of lime-mortar in the Hearmatraigh shieling, which may be the shieling imagined by Ceit for her 1978 performance.

It may be, then, that when Ceit was looking for a local setting for the story she had originally heard in Appin, moving the tale to Hearmatraigh made it more relevant and appealing to her listeners. But with this clever transfer she also skilfully preserved the cultural significance of its original moorland setting: a place out in the wilderness where dangerous supernatural creatures could overwhelm the unwary. Ceit Dix’s stories demonstrates the richness and variety of Gaelic traditional culture and offer a glimpse of how skilled storytellers adapt and localise their tales to entertain and intrigue their different audiences.